It is difficult to tell when the first slate was extracted from the Honister Slate Mine Ltd but it was probably during the time of the Roman occupation.

Fragments of Honister slate have been found at the site of the Roman Bath House at Ravenglass and Hardknott Fort.

It is possible that the Romans created the route across the fells that is known as Moses Trod to allow slate to be carried to coastal ports. Much later, the monks of Furness Abbey who owned land in Borrowdale are also thought to be early pioneers, but neither of these claims are proven.

In early times this part of Lakeland was a poor and remote land with few roads and even less habitation. The nearest town, Keswick, was half a days walk away from Honister. The hamlets of Seatoller, Seathwaite, Rosthwaite and Grange consisted of only a few farms.

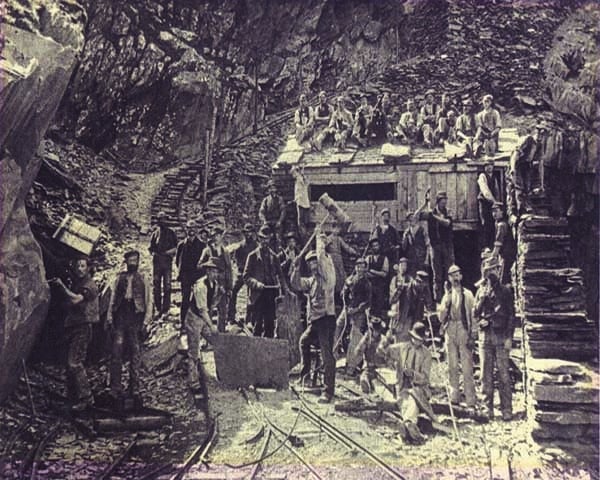

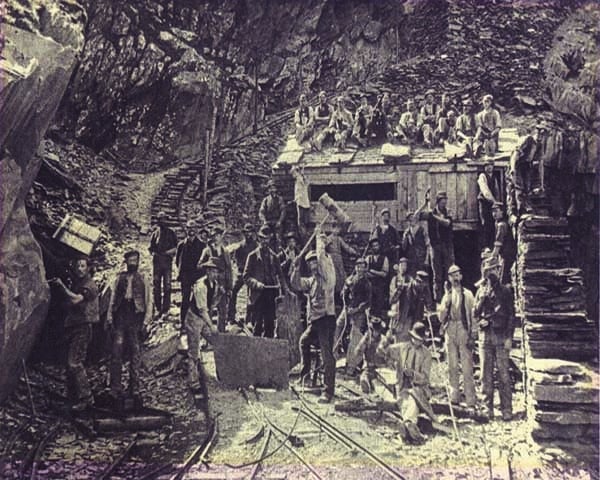

The early quarry men had no means of riding to Honister in comfort. Most walked from Keswick early on a Monday morning and lived rough on the mountains until the end of the week or even longer, working the slate by hand in all kinds of weather. Miners even walked from as far away as Egremont and Whitehaven in West Cumberland to spend the week working at the Honister Slate Mine. The first real surviving evidence of ‘slate getting’ at Honister is from around 1643. At this time the men used crude methods to prise the slate away from the surface of the Crag where the vein was exposed. The main areas where this took place is at the top of the Crag at Bull Gill and also Ash Gill, at an altitude of about 2000 feet. You can still see remains of some of the series of terraces from where the slate was taken

It is difficult to tell when the first slate was extracted from the Honister Slate Mine Ltd but it was probably during the time of the Roman occupation.

Fragments of Honister slate have been found at the site of the Roman Bath House at Ravenglass and Hardknott Fort.

It is possible that the Romans created the route across the fells that is known as Moses Trod to allow slate to be carried to coastal ports. Much later, the monks of Furness Abbey who owned land in Borrowdale are also thought to be early pioneers, but neither of these claims are proven.

In early times this part of Lakeland was a poor and remote land with few roads and even less habitation. The nearest town, Keswick, was half a days walk away from Honister. The hamlets of Seatoller, Seathwaite, Rosthwaite and Grange consisted of only a few farms.

The early quarry men had no means of riding to Honister in comfort. Most walked from Keswick early on a Monday morning and lived rough on the mountains until the end of the week or even longer, working the slate by hand in all kinds of weather. Miners even walked from as far away as Egremont and Whitehaven in West Cumberland to spend the week working at the Honister Slate Mine. The first real surviving evidence of ‘slate getting’ at Honister is from around 1643. At this time the men used crude methods to prise the slate away from the surface of the Crag where the vein was exposed. The main areas where this took place is at the top of the Crag at Bull Gill and also Ash Gill, at an altitude of about 2000 feet. You can still see remains of some of the series of terraces from where the slate was taken

For over 100 years from the early 1700’s slate was transported from the quarry workings on Honister and Yew Crags to the road below by hand-sledges. The sledges (or ‘barrows’) held up to 1/3rd of a tonne of slate. They were guided by a ‘barrow-man’ who ran in front holding the shafts to guide the sledge. After unloading the slate into carts at the road-side the barrow-man hoisted the empty sledge onto his shoulders for the walk back up to the working site.

For over 100 years from the early 1700’s slate was transported from the quarry workings on Honister and Yew Crags to the road below by hand-sledges. The sledges (or ‘barrows’) held up to 1/3rd of a tonne of slate. They were guided by a ‘barrow-man’ who ran in front holding the shafts to guide the sledge. After unloading the slate into carts at the road-side the barrow-man hoisted the empty sledge onto his shoulders for the walk back up to the working site.

Their sledge routes had to be kept in tip-top condition to maintain efficiency. This was done by laying down tons of small chippings to give as smooth a run as possible. Today it is still possible to see the faint traces of the sledge tracks and the return paths.

For over 100 years from the early 1700’s slate was transported from the quarry workings on Honister and Yew Crags to the road below by hand-sledges. The sledges (or ‘barrows’) held up to 1/3rd of a tonne of slate. They were guided by a ‘barrow-man’ who ran in front holding the shafts to guide the sledge. After unloading the slate into carts at the road-side the barrow-man hoisted the empty sledge onto his shoulders for the walk back up to the working site.

Their sledge routes had to be kept in tip-top condition to maintain efficiency. This was done by laying down tons of small chippings to give as smooth a run as possible. Today it is still possible to see the faint traces of the sledge tracks and the return paths.

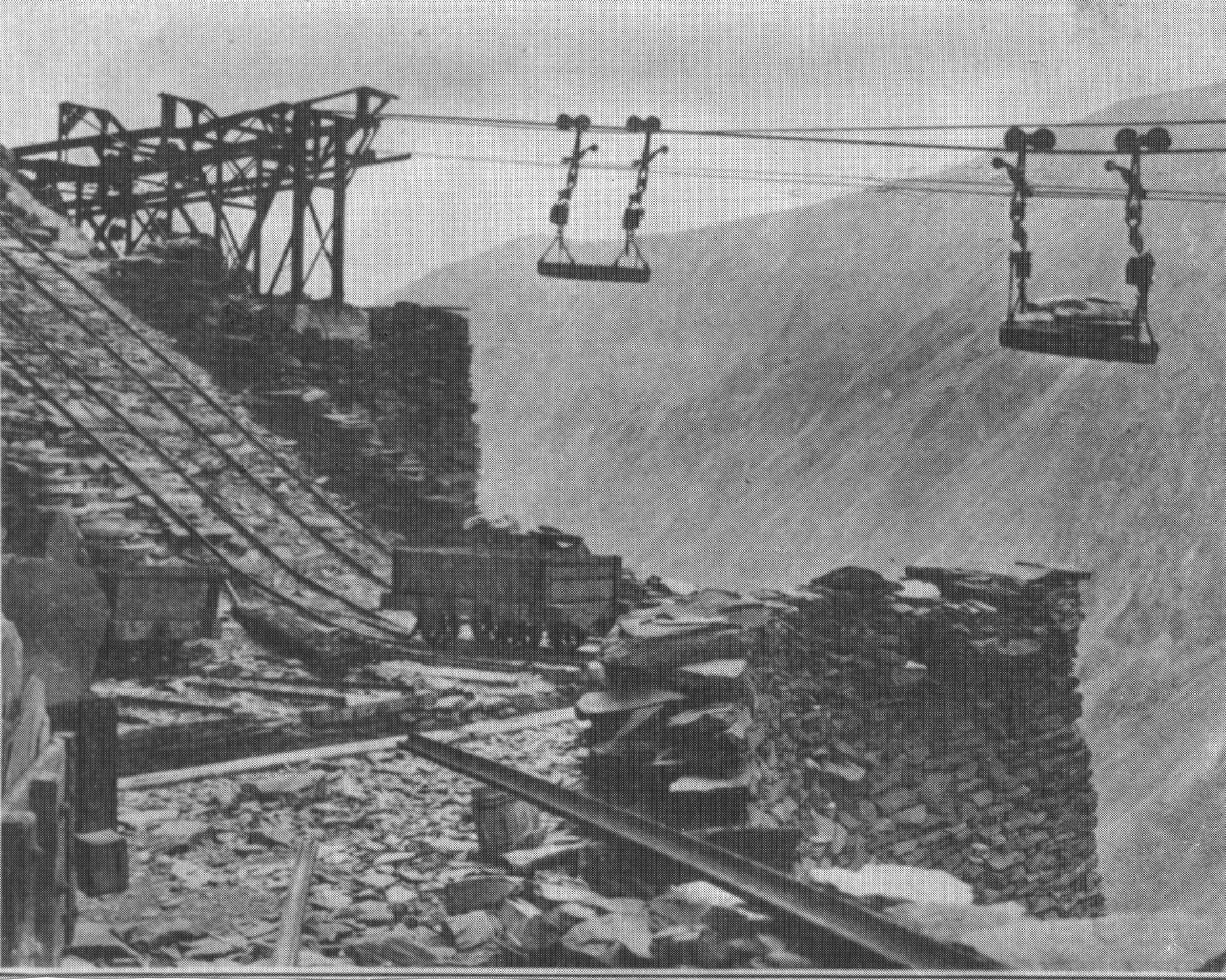

Tramways were essential for carrying heavy materials. Those at Honister were unique. The first to be commissioned in 1879 was the Yew Crag incline. It was designed to carry ‘made slates’ down to the summit of Honister Pass (The Hause). It survived the longest of all the Honister tramways, only being abandoned in 1962. During its life it was modified several times, including in 1926 when an electric winder was installed and the system improved to allow large slate blocks to be carried rather than much lighter loads of ‘made’ slates.

In 1883 work started on another formidable project – the Honister Crag Railway. The plan was to construct a line from the summit of Honister Hause, across the fell side to the foot of Honister Crag and then diagonally up the Crag face to a point almost at the top. It took 13 years to complete this remarkable venture and the Honister Crag Railway operated for about 30 years.

At the same time as the Honister Crag Railway was being constructed plans were also being laid to link Dubs Quarry above Wanscale to the summit of Honister Pass. At first it was planned to make the connection by driving a tunnel through the fell. Construction of the tunnel was started from both ends. The project was eventually abandoned because of technical difficulties despite the fact that both tunnels were well on the way to linking up. Work then started on an alternative plan – a third major tramway. It was completed in 1891. A team of four horses was used to pull trains of trucks from Dubs to the high point on the fell. From here a self activating system controlled the descent of the trucks down to Honister Hause.

For hundreds of years the only means of transport of goods between the Lake District valley communities was by pack ponies that used well established pack-horse routes across high mountain passes. These routes frequently ran from the heads of valleys and the valley-head farms became important staging points for the ponies. Although the high level tracks were well graded, they could become very dangerous in bad weather. It was only in the 19th C that improved roads removed the need for this type of transport but even today many valley-head farms are still very isolated with the only visitors being walkers passing through heading through the fells.

This was exactly the case centuries ago at Honister. For well over 300 years slate from the Honister quarries was carried by pack-horse across the high mountains to the Cumberland coast. This involved an extremely hazardous journey on steep terrain.

The route the pack trains took can still be followed today and occasionally along the way one can see deposits of broken slates showing where a load slipped and the fragile contents were lost. The route is still known as ‘Moses’ Trod’ after the quarryman, Moses Rigg, who, as well as being a skilled slate worker, operated a profitable sideline of carrying and distributing smuggled whisky from the coast which he stored in the workings on Honister Crag. From Wasdale Head the route ran along the side of Wastwater and then across West Cumberland to the Cumberland Coast near Ravenglass. Coastal boats could load cargo at this point.

Stone huts called ‘bothies’ were built by the miners to protect themselves from the elements. The bothies were built from the slate extracted from Fleetwith Pike and were only about three metres wide by four metres long. They had very thick walls to keep the wind and the rain out. They contained a fireplace, so the miners at least had some warmth. The men would live in these bothies for up to two weeks, or for as long as their supply of food lasted. Food consisted of beef dripping, bread and potatoes, simple food that would last, this would be stored in a Tommy tin.

When the supplies ran out, the men would return home. Ponies came to collect the riven slates that they had made and transport them by way of Warnscale Bottom to Whitehaven or along Moses Trod via Green Gable and on to the port of Ravenglass. These early slates were thick and crude and were used on local buildings. They did not look much like modern roofing slate, being from half an inch to an inch thick and 2-3 feet in size.

So this is how the slate industry began. It was to be a way of life at Honister for many generations. Little was to change here for nearly three hundred years.